The thief who looked forward to prison

- Sep 5, 2017

- 4 min read

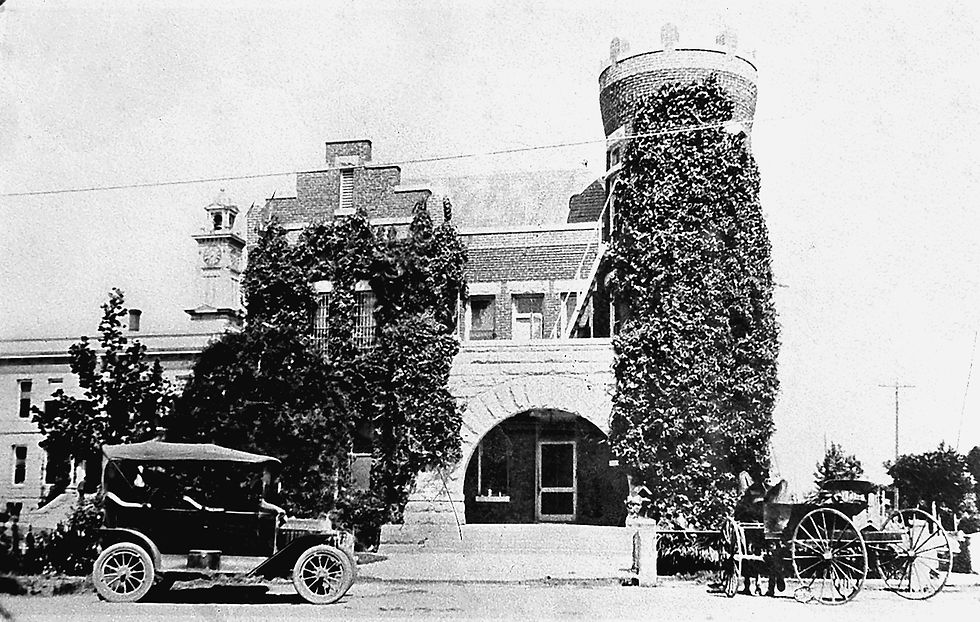

Madera County Historical Society

When Deputy Sheriff John White escorted William Sawyer out of this ivy encrusted jail, the prisoner was a happy man. Madera County’s Superior Court Judge had just thrown the rabbit into the briar patch.

The defendant rose and stepped smartly to the bench. Everyone expected him to be remorseful and contrite. After all, he had been caught stealing J.J. Husted’s horse and buggy, and back in those days in Madera such an act was certain to earn one a secure place in the state prison.

The horse thief had prepared for his sentencing. He wore a neat, blue suit, and his shoes were shined. Except for a two-week growth of beard, he had the appearance of a businessman. Surely he had groomed himself to make a good impression on the Superior Court of Madera County. Surely he was attempting to mitigate the severity of the prison term he was bound to receive.

Such reasoning, however, was far afield. William Sawyer stood before the judge that July morning in 1914, without one iota of concern for the consequences of his crime. He gazed about the room, smiled at the ladies, and in general gave no indication that he was at all sorry he was in trouble.

A murmur of disbelief spread across the courtroom. Did this character not understand the seriousness of his situation?

“Where were you born?” asked the judge.

“In Texas,” came the reply.

“How long have you been in Madera?” queried the judge.

“Just a few weeks this time,” came the answer, “but I’ve been here before.”

“What is your occupation?” asked the court.

“Cook,” answered Sawyer.

And so the pre-sentencing went, almost nonchalantly, and the observers in the courtroom were more than a little surprised. Why didn’t the defendant show any signs of nervousness? After all, he was about to be sent to prison for a very long time. The people in the court strained to find some semblance of regret. It found none.

When it came time for the judge to pass sentence, the prisoner was asked if he wanted to make a statement.

“No, sir, I don’t know that I have anything to say,” responded Sawyer, almost cavalierly.

“The sentence of this court is that you be imprisoned in San Quentin Prison for a period of 3 years,” came the judgment.

With a calm shrug of the shoulders, Sawyer thanked the judge and took his seat.

No one among those present could figure it out. The 38 year-old Sawyer had testified that he had been in trouble just one time before, and that was over a minor infraction of the law — gambling — he said. Now, here he was facing a long stretch in the state prison.

People in the courtroom were hard pressed to explain the serenity with which this novice criminal faced his upcoming ordeal. Why didn’t he seem to care?

It fell to Deputy Sheriff John White to escort Sawyer to prison. On the morning of July 21, 1914, the lawman aroused the prisoner from his bunk in the county jail and informed him that his time had come. They were scheduled to board the morning train for San Quentin.

Sawyer threw the covers back, jumped out of bed, and took advantage of the opportunity to shave, under the watchful eye of Deputy White. The prisoner’s excitement was inexplicable; it was as if he actually looked forward to walking through those prison gates. Something was wrong here!

When Sawyer and White got to the train depot, a small crowd awaited them. News of the horse thief’s benign attitude toward incarceration had spread, and although he was not a native son, a certain amount of sympathy existed for anyone who could face prison so stoically.

As the two men waited for the train, Sawyer, without handcuffs, meandered up and down the wooden planks of the platform as if he were about to leave on a vacation at the county’s expense.

He was looking his best. He was clean; his hair was combed, and his shoes were shined. Wearing a new collar and tie, Sawyer looked for all the world like a young attorney instead of a crook.

Finally the northbound train pulled into Madera, and Sawyer waved good-bye to the assembly of on-lookers. No one had been quite able to figure him out. As the cars pulled away, local Maderans left the depot shaking their heads.

Upon arriving at San Quentin, the source of Sawyer’s composure finally came to light. Much to White’s surprise, the prisoner was well known at the state prison. In fact, no less an official than the warden welcomed him at the gate. It was at that point that Sawyer’s past began to unfold.

Contrary to Sawyer’s testimony in Madera, this was his third trip to San Quentin. He was a seasoned horse thief and had first taken up residence in San Quentin 15 years before.

While in prison, Sawyer had learned all of the ins and outs of the culinary arts and had gathered considerable expertise as the prison chef. It was this skill that drew the warden to welcome Sawyer back to San Quentin. The prison chief had a special offer for Sawyer. He wanted him to take on the job of official cook for the officers of the prison.

“He is one of the best chefs going,” explained the warden to White. Turning to Sawyer, the warden said, “We’ll give you your old job back.”

At that point, the deputy understood why the prisoner had been unruffled at the 3-year sentence. He had been looking forward to his return to San Quentin. His life there was an easy one, and he liked the climate.

So Bill Sawyer donned his regimentals one more time and began work in the officer’s kitchen. He had finally come home.

Madera County had simply thrown the rabbit into the briar patch; Sawyer got lucky. If he had been born 100 later, the “Three Strikes and You’re Out” law would have taken some of the wind out of his sails.

Comments